The salt pans of the Solway Coast National Landscape are a lasting monument to a bygone industrial age.

In Anglo-Saxon times, salt production was the country’s third most important industry behind agriculture and fishing – and Cumbria, as it is known today, was one of only six areas in the country which tapped into its natural resource.

That led to a large-scale enterprise, with a virtually unbroken chain of salt pans stretching from the head of the Solway in the north, down to Millom, near Barrow in Furness, in the south.

The Solway Coast’s salt industry was boosted by the Cistercian Monks of Holme Cultram Abbey in Abbeytown.

They began shaping the landscape around them as their agricultural empire grew. They created industry at Saltcotes – which means a cluster of buildings containing salt pans – and at Newton Marsh where circular pits still gather sea water and hold it until the next high tide.

But the best preserved examples of salt pans on the Solway Coast are at Crosscanonby – and they weren’t created by Abbeytown’s monks.

Originally it was thought that they were owned and run by the influential Senhouse family of Maryport. However, a land survey carried out in 1699 shows this is not the case. Two sets of saltpans, the first, entitled ‘Netherhall Pans’, were shown on the survey a mile south of Crosscanonby. The second set of pans was located just north of the village on the coast and were entitled ‘Mr Lamplugh’s Salt Pans’. It is now thought that it was the Netherhall Pans that were owned by the Senhouses and not those at Crosscanonby.

The earliest reference to Crosscanonby Salt Pans comes in 1634 when they were let to a Richard Barwis on a 21-year lease. The Pans passed to the Lamplugh family from Ribton in 1662, first to Thomas Lamplugh and then to his son, Richard, in 1670.

From then on they were the source of some disquiet within the Lamplugh family, with two half brothers, Richard and Robert (sons of Richard senior), disputing over their ownership in 1710. Robert, who appears to have been quite wealthy, was eventually awarded the lease by the Dean and Chapter of Carlisle Cathedral.

Yet a map of Cumberland dated 1783 does not show the Netherhall Pans, which suggests they were, by this time, long abandoned.

What is now the B5300 coast road was constructed in 1824. This split the site into two halves and by 1845 it featured only the cottages and the kinch – the circular pit visible today.

The 20th century has seen significant changes to the salt pans. Between 1918 and the 1930s, holiday cottages and a caravan site grew around the area. The caravan park prospered until it was abandoned in the 1970s due to coastal erosion.

The significance of the Saltpans was rediscovered in the mid-1980s. Then, in the latter part of 1997 and early 1998, the AONB carried out major works to protect the Crosscanonby site from the threat of coastal erosion.

Rock filled gabions were built around the badly-eroded site, back-filled with more than 2,000 tonnes of material from the nearby Crosscanonby Carr nature reserve project – defences which have already proved their worth.

The site remains intact, although under constant threat from the tides, a lasting monument to an industry long departed from Solway life.

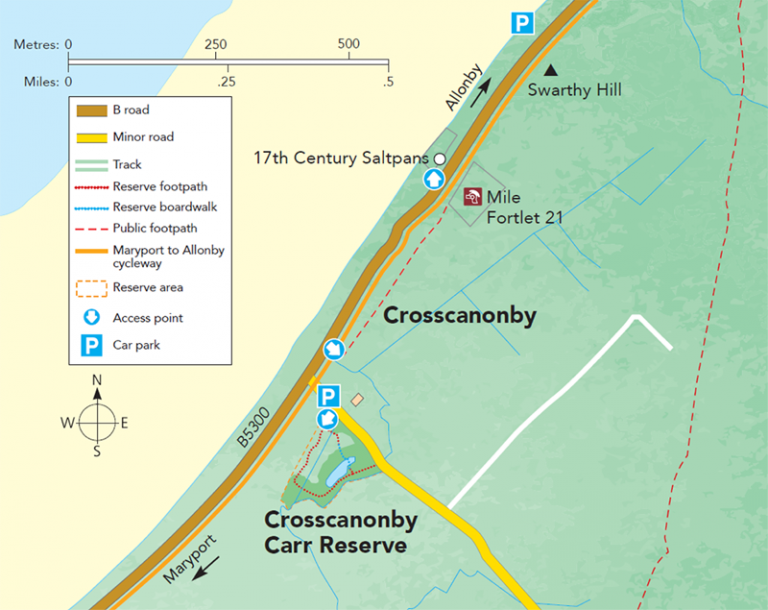

Facilities in Crosscanonby

- Parking

- Parking (including toilets) at

- Maryport 2m to the south

- Allonby 2m to the north

Did you know…?

Salt was needed to preserve foods like meat and fish – and it was vital for the farming and fishing communities on the West Cumbrian coast.

Look for…

The circular outline of the kinch pit where the slat was dried.

Getting here…

Head north out of Maryport on the B5300. You can either park at Crosscannby Carr nature reserve or at the car park just beyond the salt pans on the left-hand side.